|

The artist Mitsuaki

Tanabe brought a large drawing (9 x 1.3 meters) of a wild rice sprout

and 41 photographs related to wild rice to the International Conference

of Wild Rice held in Katmandu, capital of Nepal, in October 2002. This

conference was organized by the Green Energy Mission, a Nepalese NGO,

with the moral support of the International Rice Research Institute,

headquartered in Manila, and the Ministry of Agriculture of Nepal. Most

of the participants were scientists and agricultural experts, including

agronomists, biologists, and geneticists, so it was somewhat usual for

a person like Tanabe to participate. The artist Mitsuaki

Tanabe brought a large drawing (9 x 1.3 meters) of a wild rice sprout

and 41 photographs related to wild rice to the International Conference

of Wild Rice held in Katmandu, capital of Nepal, in October 2002. This

conference was organized by the Green Energy Mission, a Nepalese NGO,

with the moral support of the International Rice Research Institute,

headquartered in Manila, and the Ministry of Agriculture of Nepal. Most

of the participants were scientists and agricultural experts, including

agronomists, biologists, and geneticists, so it was somewhat usual for

a person like Tanabe to participate.

Since Tanabe began

making sculpture on the theme of wild rice ten years ago, he has been

devoted to the study of this plant, visiting places where it originated

and current habitats in tropical areas of Asia. In 1922, together with

the agronomist Yoichi Sato, he advocated "in situ conservation of wild

rice habitats." Since then, he has shown works of art (mainly sculpture)

that support this policy. Wild rice is being preserved through ex situ

conservation and gene banks, but Tanabe is promoting the conservation

of wild rice in its natural habitat rather than cultivating it in a

place removed from nature. Since Tanabe began

making sculpture on the theme of wild rice ten years ago, he has been

devoted to the study of this plant, visiting places where it originated

and current habitats in tropical areas of Asia. In 1922, together with

the agronomist Yoichi Sato, he advocated "in situ conservation of wild

rice habitats." Since then, he has shown works of art (mainly sculpture)

that support this policy. Wild rice is being preserved through ex situ

conservation and gene banks, but Tanabe is promoting the conservation

of wild rice in its natural habitat rather than cultivating it in a

place removed from nature.

Institutions

outside of Japan that own works of art related to wild rice by Tanabe

include: The National Museum of Contemporary Art, Republic of Korea,

Seoul; Zhe Jiang Provincial Museum and He Mu Du Ruins Museum, China;

International Rice Research Institute headquarters; the royal house

of Thailand; Pathum Thani Rice Research Center, Department of Agriculture,

Thailand; Eleanor Roosevelt High School, Maryland, U.S.A; and the Central

Rice Research Institute, India. In preparation for making these works,

he has visited Yunan province in China, the Mekong River, and Banaue

in the Philippines, a world heritage site famous for its terraced rice

fields. Institutions

outside of Japan that own works of art related to wild rice by Tanabe

include: The National Museum of Contemporary Art, Republic of Korea,

Seoul; Zhe Jiang Provincial Museum and He Mu Du Ruins Museum, China;

International Rice Research Institute headquarters; the royal house

of Thailand; Pathum Thani Rice Research Center, Department of Agriculture,

Thailand; Eleanor Roosevelt High School, Maryland, U.S.A; and the Central

Rice Research Institute, India. In preparation for making these works,

he has visited Yunan province in China, the Mekong River, and Banaue

in the Philippines, a world heritage site famous for its terraced rice

fields.

The photographs he

brought together with the drawing are pictures of the wild rice habitats

he has visited and inspected during these travels, the scholars and

scientists he has met, and conditions of wild rice sites and rice-related

customs and rituals he has observed in these areas. Tanabe's display

of art and photographs at the conference hall was designed to support

the civil organizations in Nepal who sponsored the first international

conference on wild rice. They will provide visual encouragement for

the proceedings of the conference and offer a beneficial message from

a higher perspective that transcends the narrow areas of interest of

the specialists. The photographs he

brought together with the drawing are pictures of the wild rice habitats

he has visited and inspected during these travels, the scholars and

scientists he has met, and conditions of wild rice sites and rice-related

customs and rituals he has observed in these areas. Tanabe's display

of art and photographs at the conference hall was designed to support

the civil organizations in Nepal who sponsored the first international

conference on wild rice. They will provide visual encouragement for

the proceedings of the conference and offer a beneficial message from

a higher perspective that transcends the narrow areas of interest of

the specialists.

One of the photographs,

for example, is a microphotograph of grains of wild rice excavated from

the ruins of He Mu Du, one of many ruins along the Chang Jiang (Yang-tze)

river basin, known as the oldest rice-growing area in the world. These

grains of wild rice found among grains of cultivated rice are 7000 years

old, the oldest authenticated rice grains ever. They were identified

in a joint study by a member of the staff of the Zhejiang Provincial

Museum in China and Dr. Sato after they were brought together by Tanabe.

Among the 86 grains of rice examined, five were grains of wild rice. One of the photographs,

for example, is a microphotograph of grains of wild rice excavated from

the ruins of He Mu Du, one of many ruins along the Chang Jiang (Yang-tze)

river basin, known as the oldest rice-growing area in the world. These

grains of wild rice found among grains of cultivated rice are 7000 years

old, the oldest authenticated rice grains ever. They were identified

in a joint study by a member of the staff of the Zhejiang Provincial

Museum in China and Dr. Sato after they were brought together by Tanabe.

Among the 86 grains of rice examined, five were grains of wild rice.

Judging from the high

proportion of wild rice in this sample, it is thought that wild rice

and cultivated rice were grown together in the early Neolithic period

7000 years ago. If this is the case, there must be an earlier period

in which wild rice was the main source of sustenance. The history and

culture of the people who use rice as their main food source have their

beginnings in wild rice. There are peoples who respect wild rice by

calling it "the father of rice," eating it in special rituals, and painting

pictures of rice and other crops with rice flour on the earthen walls

of their houses in the manner of the cave mural artists of Altamira.

Photographs of these are included in Tanabe's display. Judging from the high

proportion of wild rice in this sample, it is thought that wild rice

and cultivated rice were grown together in the early Neolithic period

7000 years ago. If this is the case, there must be an earlier period

in which wild rice was the main source of sustenance. The history and

culture of the people who use rice as their main food source have their

beginnings in wild rice. There are peoples who respect wild rice by

calling it "the father of rice," eating it in special rituals, and painting

pictures of rice and other crops with rice flour on the earthen walls

of their houses in the manner of the cave mural artists of Altamira.

Photographs of these are included in Tanabe's display.

There

is a strong life force emitted by the rice grains from He Mu Du ruins

that is truly amazing. The ruins are found in a low lying area, so the

old strata under the ground water level are airtight and well suited

to the preservation of buried artifacts. Even so, it was remarkable

that the 7000-year-old rice grains had kept a golden color until they

were excavated. There is something awe-inspiring about the appearance

of the wild rice grains photographed under a microscope. They had carbonized

after excavation but were gold plated by a special process for the photograph.

Traces of the pointed beard are clearly visible, and there is a sense

of vitality in the bristles and rigid bumps and hollows on the surface.

The fibrous material covering the surface is seen under the microscope

to be intricately intertwined, presenting a grotesque appearance that

is as much like an animal as a plant. There

is a strong life force emitted by the rice grains from He Mu Du ruins

that is truly amazing. The ruins are found in a low lying area, so the

old strata under the ground water level are airtight and well suited

to the preservation of buried artifacts. Even so, it was remarkable

that the 7000-year-old rice grains had kept a golden color until they

were excavated. There is something awe-inspiring about the appearance

of the wild rice grains photographed under a microscope. They had carbonized

after excavation but were gold plated by a special process for the photograph.

Traces of the pointed beard are clearly visible, and there is a sense

of vitality in the bristles and rigid bumps and hollows on the surface.

The fibrous material covering the surface is seen under the microscope

to be intricately intertwined, presenting a grotesque appearance that

is as much like an animal as a plant.

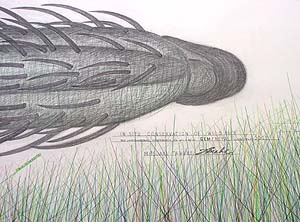

Tanabe's drawing effectively

expresses this mysterious life force of the rice grain. He intended

this drawing as an accurate representation to be presented to scientists,

placing the model rice grain under a microscope and drawing it from

close and careful observation. However, the result is not an ordinary

realistic illustration of the kind that appears in botany textbooks

but a bold form extending across the large sheet of paper like an animal

ready to attack, hair on end, teeth bared, and sharpening its claws.

There is more to it than super-realism. The artist has tried to give

visual form to the invisible power contained within a single grain of

rice that cannot be seen with a camera or under a microscope. Tanabe's drawing effectively

expresses this mysterious life force of the rice grain. He intended

this drawing as an accurate representation to be presented to scientists,

placing the model rice grain under a microscope and drawing it from

close and careful observation. However, the result is not an ordinary

realistic illustration of the kind that appears in botany textbooks

but a bold form extending across the large sheet of paper like an animal

ready to attack, hair on end, teeth bared, and sharpening its claws.

There is more to it than super-realism. The artist has tried to give

visual form to the invisible power contained within a single grain of

rice that cannot be seen with a camera or under a microscope.

The wild rice of the

Chang Jiang river basin eventually disappeared because of changes in

climate, but the cultivated rice that inherited its indomitable vitality

showed great adaptability. Through the patient labor of many people,

it spread and conquered the warm regions of the world. The wild rice of the

Chang Jiang river basin eventually disappeared because of changes in

climate, but the cultivated rice that inherited its indomitable vitality

showed great adaptability. Through the patient labor of many people,

it spread and conquered the warm regions of the world.

Tanabe's drawing is

a large image, blown up to a size that reflects the artist's deep love

and respect for this grain of wild rice, a source of sustenance and

a concentrated form of life. The image expresses the generosity and

depth of his thinking, observing and understanding the significance

of preserving the habitat of wild rice and passing it on to later generations. Tanabe's drawing is

a large image, blown up to a size that reflects the artist's deep love

and respect for this grain of wild rice, a source of sustenance and

a concentrated form of life. The image expresses the generosity and

depth of his thinking, observing and understanding the significance

of preserving the habitat of wild rice and passing it on to later generations.

The value of Tanabe's

thought and art were recognized by Dr. Klaus Lampe, former director

of the International Rice Research Institute. Tanabe was invited to

the institute to create a large sculpture, Momi 1994, Sprouting Wild

Rice, for the new Learning and Vistors Center, using 8 tons of red lauan

wood. On the occasion of a research conference, Japan IRRI Day, in Tokyo

that same year, Tanabe was asked by Dr. Lampe to create a display of

his own design in Nikkei Hall, the site of the conference. Tanabe made

a new drawing of a wild rice grain of the same size as the current work

and displayed two forged stainless steel sculptures portraying wild

rice seeds to create an appropriate atmosphere for the meeting. Then,

after a proposal by Tanabe and the agreement of everyone present, these

works were presented to Her Royal Highness Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn

of Thailand, the sponsor of the conference. The value of Tanabe's

thought and art were recognized by Dr. Klaus Lampe, former director

of the International Rice Research Institute. Tanabe was invited to

the institute to create a large sculpture, Momi 1994, Sprouting Wild

Rice, for the new Learning and Vistors Center, using 8 tons of red lauan

wood. On the occasion of a research conference, Japan IRRI Day, in Tokyo

that same year, Tanabe was asked by Dr. Lampe to create a display of

his own design in Nikkei Hall, the site of the conference. Tanabe made

a new drawing of a wild rice grain of the same size as the current work

and displayed two forged stainless steel sculptures portraying wild

rice seeds to create an appropriate atmosphere for the meeting. Then,

after a proposal by Tanabe and the agreement of everyone present, these

works were presented to Her Royal Highness Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn

of Thailand, the sponsor of the conference.

Immediately

after the conference, in situ conservation of wild rice was adopted

as a special project of the royal house of Thailand, and Tanabe participated

in this project by creating two wild rice sculptures for the Pathum

Thani Rice Research Center in Thailand. One of these sculptures, created

in 1997, was a large outdoor monument to wild rice. It was made of forged

stainless steel and measured 33 meters in length. Immediately

after the conference, in situ conservation of wild rice was adopted

as a special project of the royal house of Thailand, and Tanabe participated

in this project by creating two wild rice sculptures for the Pathum

Thani Rice Research Center in Thailand. One of these sculptures, created

in 1997, was a large outdoor monument to wild rice. It was made of forged

stainless steel and measured 33 meters in length.

The mission of in

situ conservation of wild rice is specifically to preserve the natural

habitat of wild rice, which is gradually being destroyed in recent years

because of excessive economic development. From a wider perspective,

however, it is also a proposal for overall preservation of the natural

environment and the diversity of life. The natural habitat of rice,

a water plant, is mainly found in wetlands, around lakes, rivers, and

marshes, so this movement is inevitably involved with the many environmental

issues related to water. These habitats are also watering places and

foraging areas for animals, including elephants, rhinoceroses, and water

buffalo. Many different kinds of animals are born in or come to these

places. In situ conservation is important for maintaining the diversity

of the animal population as well as preserving wild rice. Unfortunately,

there are as yet no scientists specifically studying the varied animal

life of wild rice habitats. The mission of in

situ conservation of wild rice is specifically to preserve the natural

habitat of wild rice, which is gradually being destroyed in recent years

because of excessive economic development. From a wider perspective,

however, it is also a proposal for overall preservation of the natural

environment and the diversity of life. The natural habitat of rice,

a water plant, is mainly found in wetlands, around lakes, rivers, and

marshes, so this movement is inevitably involved with the many environmental

issues related to water. These habitats are also watering places and

foraging areas for animals, including elephants, rhinoceroses, and water

buffalo. Many different kinds of animals are born in or come to these

places. In situ conservation is important for maintaining the diversity

of the animal population as well as preserving wild rice. Unfortunately,

there are as yet no scientists specifically studying the varied animal

life of wild rice habitats.

In order to comment

on this situation, Tanabe has been using symbolic animals - birds, insects,

centipedes, and spiders -- as the subjects of his recent work. Examples

include the great snake of Mekong River (installed on the grounds of

Yokohama Municipal Shimoda Elementary School) and the figure of the

large lizard with the word "Crisis" engraved on its legs. These reptiles

are symbolic because they signal the danger of extinction. There are

a number of interesting snapshots connected with these recent works

displayed in the conference center in Katmandu. In order to comment

on this situation, Tanabe has been using symbolic animals - birds, insects,

centipedes, and spiders -- as the subjects of his recent work. Examples

include the great snake of Mekong River (installed on the grounds of

Yokohama Municipal Shimoda Elementary School) and the figure of the

large lizard with the word "Crisis" engraved on its legs. These reptiles

are symbolic because they signal the danger of extinction. There are

a number of interesting snapshots connected with these recent works

displayed in the conference center in Katmandu.

One photograph shows

the habitat in Bhubaneshwar, East India. A thin man is seen wandering

through the parched wetlands in the dry season, parting dry stalks of

wild rice with a stick. Wearing a white turban and a white robe, he

has the appearance of someone like Moses or Aaron from the Old Testament.

He has the serene air of someone who lives in harmony with nature, a

grace that almost seems religious. One photograph shows

the habitat in Bhubaneshwar, East India. A thin man is seen wandering

through the parched wetlands in the dry season, parting dry stalks of

wild rice with a stick. Wearing a white turban and a white robe, he

has the appearance of someone like Moses or Aaron from the Old Testament.

He has the serene air of someone who lives in harmony with nature, a

grace that almost seems religious.

However,

this man is not a prophet or anything of the sort. He is a farmer looking

for tortoises, poking the ground with his stick as he walks along. And

this seemingly innocuous (or pleasurable) action could very well lead

to a crisis, the extinction of the animals. However,

this man is not a prophet or anything of the sort. He is a farmer looking

for tortoises, poking the ground with his stick as he walks along. And

this seemingly innocuous (or pleasurable) action could very well lead

to a crisis, the extinction of the animals.

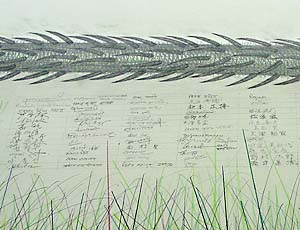

Tanabe wishes to dedicate

the drawing, signed by all the participants in the conference to indicate

their support for in situ wild rice conservation, to the abundant natural

environment of Nepal, calling it Himalayan Project No. 1. Tanabe wishes to dedicate

the drawing, signed by all the participants in the conference to indicate

their support for in situ wild rice conservation, to the abundant natural

environment of Nepal, calling it Himalayan Project No. 1.

|

Å@

Å@

Å@

Å@